Easy Rider

With perfect timing, the film Easy Rider was released in 1970. Just as the 1960s had flung the doors of perception wide open, Easy Rider showed how many minds had remained firmly shut. The term Easy Rider is US slang, which according to some is for a prostitute, while others claim it is for a man who lives off the takings of prostitutes. Either way, it was an irony perhaps missed by UK audiences. Its UK release had followed hot on the heels of The Wild One, which had been postponed by the censors. Being some fifteen years old already, The Wild One had looked comparatively jaded. Easy Rider, however, had a resounding impact in the UK and US. The ideologies it conveyed reflected more relaxed attitudes, among and towards Bikers. The contentions between motorcycle gangs were being replaced by the greater brotherhood. These were political times, and subcultures were beginning to be constructed out of social rather than entirely selfish motives.

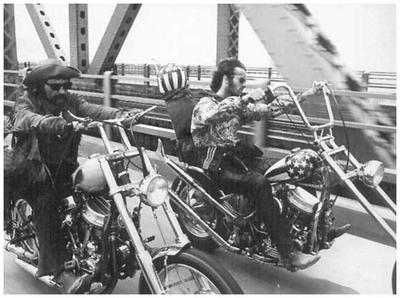

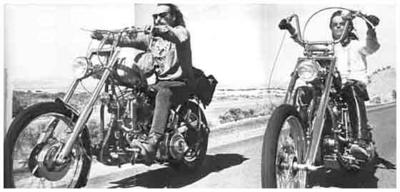

Although it was made in America, Easy Rider successfully engaged with UK Biker-Hippy audiences. An analysis of this film for a university study is where this book began. The film reflected a joining of Bikers and Hippies that had occurred in the real world, and was aimed directly at them. It was a visual, almost non-verbal experience. A plot was replaced by a string of scenarios that would be familiar to the audience. The story covers the encounters of Wyatt Earp (played by Peter Fonda), and Billy The Kid (played by Dennis Hopper), as they travelled from California to New Orleans. The Harley-Davidson choppers they rode endeared the film and the two central characters to Biker audiences. A third character, George Hanson (played by Jack Nicholson) joined them briefly. Their search for freedom ended in their deaths, caused by straight, or ordinary people. This drove home the message of the film: peaceful people versus mass-society.

Through the interviews conducted for the university study, notable distinctions between Bikers, Hippies, and Rockers, and those who were not bona fide members of these subcultures, were made. The main features were that:

Through the interviews conducted for the university study, notable distinctions between Bikers, Hippies, and Rockers, and those who were not bona fide members of these subcultures, were made. The main features were that:- Bikers are people who find a sense of individual freedom and a feeling of unity through the enjoyment of motorcycling.

- Hippies are politically aware and believe in societal freedom.

- Rockers are the cultural descendants of Teddy-Boys, who got into bikes through the rock and roll scene, whist it is also true that some Bikers became Rockers.

- Others, though similarly dressed, weren’t the genuine item. They engaged in the image, not the ethos, on a part-time basis.

Some Biker types went to see Easy Rider expecting to see footage of motorcycling. The steady pace of the bikes throughout was a let-down for the speed-freak. Other Bikers were aware that the film had a message, and went to enjoy it, if not to check that the message met with their own ideals - and approval. Hippy interest was also engaged through the message of freedom. Postmodern films are said to be low culture, like TV trash. But Easy Rider became high culture and singular in meaning, at least to its intended audience (self again, thankfully included). It showed how attempts to create peaceful culture were destroyed through narrow-mindedness and discrimination. By entertaining Biker-Hippies through their own culture, the film not only gratified their needs, but also echoed their own social comment, by portraying their beliefs.

For the others, including the general public, it was purely a cinematic experience, and their involvement ended as the credits rolled up. Its appeal for these mass audiences was situated in curiosity. Their partial pleasure was to watch the UK Bikers and Hippies watching a film about US Biker-Hippies. They wished to view strange worlds, or were buying into the mystique of subculture, rather than being pro-active in its development.

The books and other films about Outlaws coloured some people’s expectations of what the film would be about. But, unlike in previous road movies, the violent image of Bikers was not reflected. Instead, violence came from members of straight society, enacted upon the Biker-Hippies. Through this kind of incident, the film explored a truer side of Biker-Hippy culture. It represented a shift in the us-and-them paradigm, through the elusiveness of liberty in an industrial world.

Film making and society were undergoing crucial changes. These factors prepared the audience for a new movie genre. Social analysts had agreed that they had to look at new situations in new ways. The films of the time also had to be analysed differently. Earlier movies would allow the camera a lingering gaze at heroes and heroines, but in Easy Rider, the camera work is more evenly distributed among scenery and other characters. Postmodern filmmaking relied on joining segments together, into a patchwork. This gives a different feel towards what is going on in the film, and provides a different aspect to how the minds of the audiences worked.

Film making and society were undergoing crucial changes. These factors prepared the audience for a new movie genre. Social analysts had agreed that they had to look at new situations in new ways. The films of the time also had to be analysed differently. Earlier movies would allow the camera a lingering gaze at heroes and heroines, but in Easy Rider, the camera work is more evenly distributed among scenery and other characters. Postmodern filmmaking relied on joining segments together, into a patchwork. This gives a different feel towards what is going on in the film, and provides a different aspect to how the minds of the audiences worked.Rather than feeding aggression, it described alienation through the Big Idea. This was an ideology based on freedom, that formed the adhesive for the combined Biker-Hippy cultures. Hopper, Fonda, Nicholson and others involved in the movie considered themselves part of it, giving the film a quality of social comment over an undercurrent of dissent. This connected directly with the minds of its subcultural audiences, and spoke in new ways to anyone who felt ostracized by or apart from society. Easy Rider was within but not of the mass media.

It has been suggested that movies extend one single sense in high definition. Through this, audience participation is supposed to be restricted. It causes the audience to feel isolated, which would result in the ‘detribalising’ of minority cultures. This meant that Easy Rider would detract from, rather than add to the stability of the subcultural audience. However, through changed cinematic technique and repositioned ideologies, it promoted a bonding instead. By minimalising the heroes, it struck up a political empathy with the story. The people in the university study mostly felt that though the story was not true to life, the film lived up to their expectations. It used the stereotype without patronising them, which gave realism to the Big Idea.

The sound track was a crucial element in the understanding of the story, and in the film’s popularity. The lyrics in Born To Be Wild, by Steppenwolf, embody a motif of freedom shared by the film and its intended audiences. The line: “Like a streak of lightnin’/Heavy metal thunder/Racin’ with the wind/And the feelin’ that I’m under.” - captured the essence of Biker-Hippy beliefs. The music alone celebrated their ideologies and reflected their thinking. It created excitement among them; they were united against the straight people, and peaceful revolution seemed imminent in real life.

Another performer used on the soundtrack was Jimi Hendrix, whose outrageous clothes suited the Hippy scene, while his aggressive guitar sound excited Bikers. His song, If Six Was Nine, was played over bike-riding shots through a town. The lyrics struck out at straight society: “White-collared conservative walking down the street/They point their plastic finger at me/They hope that soon my kind will drop and die/But hey/I’m gonna wave my Freak flag high.”

Society and the media regarded bikers and Hippies as freaks, but people who considered themselves individuals were using the term freak. The two main characters were insulted by hicks calling them freaks. This is ironic, as the hicks wouldn’t understand that it was hip to be called freak. No-one minded the freak epithet; it was more ambiguous than other stereotyping. Hendrix’s If Six was Nine also encapsulates this mood by stating: “If all the Hippies, cut of all their hair/I don’t care/‘Cos I’ve got my own world to live through/And I ain’t gonna copy you.” Hippies had started out as individuals, but as the high street shops began selling ready-made Hippy clothes, the natural fluidity of cultural evolution moved them along. London’s fashionable Carnaby Street was regarded as far from reality. It was a consumer outlet, not the soul of Hippiedom. Easy Rider went with that kind of thinking, and spoke the language of the freak, not the weekend trendy.

The clothing worn by the characters in the film was also an astute choice that reflected realism. Hippy and Biker cultures had used a mixture of images like 1920’s dresses, flying jackets and other clothes, that were seemingly out of context. Known as bricolage, this gave out a message that was incongruous. The Billy character went for the fringed suede jacket and cowboy hat. The fringed jacket is an item of American Indian clothing adopted by both US and UK Hippies and Bikers. American Indian culture held them fascinated; the Indians were their idylls of freedom. Paradoxically, country-hicks (who might also wear fringed suede jackets) were disliked by American Hippies, while at the same time an element of progressive country music (like The Byrds) was enjoyed. It was the wild bush-dweller ideal, not the xenophobic isolation of the backwoods that appealed to youth.

Bikers understood the significance of borrowing Hippy clothes, but it confused the rest of the world. The convergence of these subcultures became a layered patchwork (just like the jeans they were wearing). Understood by its members, it compounded the attitude of normal people who still insisted on a pretence of gender mix-up when they encountered longhaired men. One of the thugs in the film confirms this, saying of Billy: “I bet he squats to pee.”

Wyatt’s clothes and bike were bedecked with the Stars and Stripes. Because the film sits astride the Atlantic, the meaning of the flag is confused. American Hippies despised and burned it during anti-Vietnam War protests. At the same time, British Bikers associated it with Harley-Davidson motorcycles, which some liked. They wanted in with US Biker culture, believing the American grass was greener. But being free in the UK did not involve being shot, which is how Wyatt and Billy die in the film, and how many US youths were dying in real life. The anger of UK Biker-Hippies wanted this heroism, while their philosophy despised its inherent violence.

Easy Rider’s vocabulary includes metaphors like scene and cool. Once ordinary people began using hip language, it lost its value. Fortunately for the makers of Easy Rider, their Biker-Hippy audience did not regard Wyatt and Billy as ordinary.

In his forthright and accurate book, Bikers: The Birth of an Outlaw, Maz Harris described an air of excitement surrounding the film. He said: “Easy Rider gripped our world by the neck and shook it around. Nothing was ever the same again. It provided a clarity of image, a style which hitherto had been lacking, and it banished everything that had gone before into total obscurity.” As a founder of the UK Hell’s Angels, Harris’ lucid comment exposes that loyalty to the ideals of the early fraternities that genuine Bikers cling to.

In another book, about the making of Easy Rider, Lee Hill said: “Easy Rider uncannily documents an era that was in the process of ending before it ever truly began.” He refers to the death of the Biker and Hippy stereotypes, which further shows that people were beginning to understand genuine as opposed to media-fabricated Bikers. He says how they were evolving from and splintering into other subgroups in the same moment. Changes were happening, however, the most poignant aspect of Easy Rider was that someone had at last identified the true nature of the whole alternative crisis.

Cultural studies and films have previously cast Bikers as working class people who are often deviants. The Wild One depicts an American example. But a cross-section of any Biker gathering represents a broad selection of social backgrounds. People within the Hippy movement also came from different social strata. Both groups were basically ordinary people, the major difference (between them and straight society) being that they would stand up for their rights. The only class element in Easy Rider is represented by the restraints of income. In the opening scene, the small bikes ridden by Wyatt and Billy represent the Biker desire for larger (more expensive) ones. They also needed money to be free from the ties of having to earn a living.

They achieve this by selling cocaine. There are ironies between this and the Steppenwolf track, The Pusher, played immediately following the drug-dealing episode at the beginning of the film. The lyrics concern a hatred for addictive-drug dealers: “Well I smoked a lotta grass/Mm-lord I popped a lotta pills/But I never touched nothin’/That my spirit could kill.” With the chorus: “God damn/God damn/The pusher.” While this is an admission to the use of soft drugs, it is a denial of addictive drugs. The tensions within this moral dimension are highlighted in the film’s drug-deal, because cocaine is regarded as addictive: by Wyatt, Billy and the intended audience. Drug taking occurs in the film as a leisure activity and a mystical experience. Rather than being enacted as shallow and cocky, it represents that which Timothy Leary had expounded in the 1960s; “Turn on, tune in and drop out.” Bikers recognised this despite their hedonistic reputation.

Used later in the film, the lyrics of the Byrds song Wasn’t Born to Follow, are at one with nature and drug-oriented: “Where the trees have leaves of prisms/That break the light in colours/That no-one knows the names of.” Nature and the environment were notable Hippy concerns, however motorcyclists were already keen outdoor types, if not enthusiastic conservationists.

As they set off on their new choppers, Wyatt noticed his watch had stopped and he threw it away. A Hippy interviewee for the study said that: “This signals not just a break from material possessions, but also a disregard for time itself, something natural to a free spirit.” It also inferred that with the money Wyatt and Billy now had, they were free of financial constraint. Whether coincidental or not, the watch incident occurs among some standing stones. These have long been associated with a prehistoric knowledge of time and astronomy. Because of the interest Hippy culture had in such things, it could easily have been deliberate: time (the watch) discarded in a timeless place.

The myth of free love was accurately represented, when Billy and Wyatt stayed at a Hippy commune. They met girls, went skinny-dipping with them, and as a natural consequence it is inferred but not physically shown that they made love. This was how it actually worked, not in the way people were imagining it: any male with a flash car or bike and/or drugs thought they could attract females and lure them into sexual encounters. Free love was just a natural progression from a chemically right encounter, not something that could be grabbed off the street - the latter being purely sexual favours.

The third character, George Hanson, turned out to be quite hip for a drunkard and small-town lawyer. He was socially and politically aware, and understood American greed and the manipulation of social mores to meet selfish ends. In a brief speech he encapsulated the Big Idea, saying: “Talkin’ about freedom and bein’ free - that’s two different things. I mean, it’s real hard to be free when you are bought and sold in the market place. ‘Course don’t ever tell anybody they’re not free, cause then they’re gonna get really busy killin’ and maimin’ to prove to you that they are. Oh yeah, they’re gonna talk to you and talk to you about individual freedom, but they see a free individual, it’s gonna scare ‘em.”

George’s part, though short-lived, was indispensable. The essence of his speech and the movie was enhanced by the lyrics of the song It’s alright ma (I’m only Bleedin’), by Bob Dylan, which stated: “Keep it in your mind and not fergit/That it is not he she them or it/That you belong to.” The freedom factor on the street was very much alive, and was aired in connection with the George character.

A scene in a cafe involved some young girls who are attracted to the nomadic Bikers. But other patrons decided they didn’t like their appearance. They later attacked the three characters while they slept. This resulted in George’s death, which was especially poignant because he had only just decided to join Wyatt and Billy in a bid for freedom, and having tried marijuana, would have died stoned. It was also ironic, in that scared individuals had murdered him. After his death, Billy expressed relief, at having not been killed in the attack. He said: “We made it.” But Wyatt replied: “We blew it.” He felt partly to blame for George’s death; it was their misadventure that had caused it, implying a moral responsibility. He was also inferring that through the drug dealing, they’d sold out, and been corrupted by capitalist incentives.

Prior to the attack, George had given Wyatt and Billy the address of Madame Tinkertoy’s whorehouse in New Orleans. When they later arrived in Orleans, they shared LSD with two girls from the brothel. To go with prostitutes should have undermined their moral if not their masculine credibility, but for the gesture it made, in memory of George. During this psychedelic experience, Wyatt had premonitions of their death. This drug-trip scene stands in for the clichéd cinematic dream-sequence. Rather than wash the screen with out-of-focus waves, it was peppered with rapid cuts from within, before and after the scene. According to some people interviewed, this confused the plot a little, because the visual and sound effects were trying to simulate the LSD experience. It included other cinematic break-aways from effects like the fade, by showing forward-flashes of a burning bike instead. Its function as a foresight only becomes apparent at the end of the film. This kind of mental athleticism has since become more commonplace in movie watching.

In real life, Fonda’s mother had committed suicide. He was goaded by Hopper to talk about this in a stoned voice for the trip scene. Recognising a drugged voice created realism for the Biker-Hippies, and morbid curiosity for the voyeuristic others (especially as Wyatt and Billy copulated with the girls in a cemetery, whilst an off-screen voice prayed). On the subject of drugs, all those in the study regarded marijuana as safe and cocaine as dangerous because it was potentially addictive. They revealed that LSD is OK, but in the wrong hands (or minds) it could be trouble.

In real life, Fonda’s mother had committed suicide. He was goaded by Hopper to talk about this in a stoned voice for the trip scene. Recognising a drugged voice created realism for the Biker-Hippies, and morbid curiosity for the voyeuristic others (especially as Wyatt and Billy copulated with the girls in a cemetery, whilst an off-screen voice prayed). On the subject of drugs, all those in the study regarded marijuana as safe and cocaine as dangerous because it was potentially addictive. They revealed that LSD is OK, but in the wrong hands (or minds) it could be trouble.

At the end of the movie, there was sad irony when Wyatt and Billy met their deaths. A country hick in a pick-up shot them as they rode along. The mood does not call for revenge, but alludes to their finding freedom in death. This represented the Biker idiom, Death or Glory. As one interviewee commented: “Had they been killed in a horrific motorcycle accident, it would have simply been fate. But because they were blown away in a senseless, violent murder, we are angry, yet numbed.” This compounded the dissent of both subcultures towards the intolerant nature of mass-society. The lyrics to Roger McGuinn’s song, Ballad of the Easy Rider, acted as a closing statement: “All that he wanted/Was to be free/And that’s the way it/Turned out to be.”

Through Easy Rider’s trans-Atlantic shift we can see how the recent subcultural origins were becoming global - following in the trail of the earlier biking expansion. After a brief peak, they appeared to be succeeded by subsequent youth movements. However, this was mostly an illusion created by the mass-media. While they focused on the next generation, Hippy culture lived on, influencing subsequent generations like the New Romantics. And biking has remained constant as ever, in greater or lesser numbers, whether it is fashionable or not.

Easy Rider took elements of subculture and melded them into a formula that represented the position of its audience in society. Their appearance, life-style and beliefs were up there on the big screen, and although the protagonists were killed, even because of it, it still poked the eye of straight society. Not all the Biker-Hippies who saw it knew someone who’d been killed, but they’d all been criticised or harangued for their appearance and beliefs. The stereotype had now shifted, from Outlaw or Rocker to Biker. It is here, that the mass-media image became stuck. Meanwhile, Biker and Hippy-types, out of all cultural groups, seem the only ones capable of realising that ancient wisdom is not an anachronism.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home